Pilot whale hunt dates back to the beginning of the Norse settlement of the Faroes c. 1200 years ago. Screenshot from the book “Pilot Whaling in the Faroe Islands” by Jóan Pauli Joensen.

The pilot whale hunt in the Faroe Islands will end in the not too distant future. In this the Faroese are mostly in agreement, even many of those who are pro-whaling. But until that happens, whale advocates will need to be patient.

(Part one of a three-part series)

“It won’t bother me when it ends.” His hands relaxed on the steering wheel, David* is on his way from the airport in Vagar to Tórshavn, the capital of the Faroe Islands. It’s a drive through a spectacular, fjord-carved landscape. The 25-year-old taxi driver is speaking of the grindadráp, the traditional Faroese pilot whale hunt.

Yes, he has already killed pilot whales, he admits.

If there’s a catch around here and I have no whale meat in the freezer, I will take part.

David’s attitude is representative of many Faroese. Surveys in recent years show that a majority of the Faroese population is still behind the whaling which is vehemently criticised internationally. But at the same time most of the younger and middle-aged locals would shed no tears at the end of the hunts.

I hear this opportunistic attitude repeatedly during my stays in the Atlantic islands at 62 degrees north. The pilot whale hunting is an exciting, bloody spectacle that brings some diversion to many residents, in perhaps the most remote corner of Europe – and considerable quantities of free whale meat, as well as international attention.

An adrenaline rush related to the hunting instinct of the men of a tiny, close-knit island nation which survived for centuries on little other than fish, sheep, birds – and whale meat.

Stunning beauty. The Faroes are perfect for ecotourism, with breathtaking landscapes and a potential to see whales and dolphins at sea, among birds and other marine wildlife. Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar

“It will stop on its own”

“The grindadráp will stop on its own” added David after a while, as he entered a long, photo controlled toll-tunnel. “In something like 10 to 15 years. For that, activists who want to tell us what to do are not needed. On the contrary.” This too, is how many Faroese see the issue.

The road connects the island of Vagar to the main island of Streymoy by a spectacular tunnel under a mile-wide stretch of water. David laughs,

Whaling for the youngsters? They’re not that interested in whale hunts. If they have a good computer game, you can no longer get them out of the door.

Innovation, enterprising people and the latest technology have brought the semi-autonomous island republic, which is under Danish administration, a very modern standard of living. So the grindadráp may well seem like a bizarre anachronism, if you do not take Faroese history into account.

And the pilot whale hunt is no longer really ‘traditional’. Up until less than 100 years ago, men in rowing boats drove marine mammals into the killing bays using pure muscle power. Today an armada of modern, high-powered and sonar-equipped motor yachts, speedboats and jet skis chase the whales.

Mercury in the meat

In Tórshavn the mood is peaceful and relaxed, as always, even when the weather requires woollen sweaters or wind-stoppers to have a coffee outdoors.

Kristina, who serves in a cafe at the harbour, also provides information frankly when asked about her stance on the pilot whale hunts – and the presence of activists from the organisation Sea Shepherd. Dozens at a time are staying throughout the summer in the Faroe Islands this year, and have brought along an impressive array of boats and vehicles.

Kristina is quite alienated by theirfierce looking outfits and finger-pointing behaviour, but respects their stay on the islands and their stance, even though she does not agree with them. “For me, the grindadráp is nothing more than another form of fishing,” says the 28-year-old. “I grew up with this tradition and I do not know any different.”

Today Kristina enjoys whale meat but with great caution. She rarely eats it and often regrets it afterwards.

I know about the high levels of mercury and other pollutants in the meat and blubber of pilot whales. Women especially take the official warnings seriously and refrain from eating it before and during pregnancy and lactation.

Many threats

She has never thought about what the mercury toxicity, which results from marine pollution, means for the pilot whales. It has been documented in killer whales (also known as orcas), which are the closest relatives to pilot whales, that the mothers transfer large amounts of pollutants through their milk to their young and therefore very often lose the first calf.

There are numerous other threats to whales to add to this tragic result of man-made pollution: overfishing, entanglement and drowning in nets, by-catch (estimated 300,000 whales per year), underwater noise, climate change, urban sprawl of coastal developments and more.

So it is not wise to additionally burden by hunting,whale populations that so little is known about. Kristina now understood, saying: “So perhaps it’s time to say farewell to the grindadráp.”

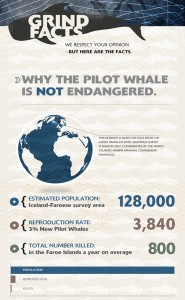

Mortality rate is missing. This chart gives the misleading impression that the pilot whale population grows by approx 3,000 each year. Source: Grind Facts

Demand Drops

The proponents of the pilot whale hunt see it differently. In June 2014 the ‘Faroese Pilot Whalers Association’ launched a new website providing information about the drive hunt. It is misleading however, if one is not careful, not least because the data provided is incomplete.

For example, the website states the estimated total population of pilot whales to be 128,000 in the North Atlantic area around the Faroes and Iceland. Births would mean 3,840 new animals each year, while the Faroese kill an average of 800 each year.

This gives the impression that the pilot whale population is increasing by over 3,000 animals each year, but there is no mention of the natural mortality rate, or of how many die from the man-made threats mentioned above; both are missing. Thus the figures are loaded in favour of the hunters and worthless.

Ole, aged about 55, who along with grind also likes to eat meat from fin whales or belugas from Greenland, also makes a remarkable assessment. He too thinks that the grindadráp will last for another 10 to 15 years.

He believes the drive hunt could end rather abruptly:

If one day after a hunt a dozen pilot whales were left to rot, because no one wanted their meat, then the Faroese would consign the pilot whale hunt to the history books.

Rúni Nielsen, a moderate Faroese opponent of the grindadráp, notes on the same subject that last year, when so many dolphins were killed (a total of 1,534), some meat shares which had been allocated to the locals in the respective regions, had not been collected. “This, even in spite of repeated calls for takers on the radio.”

That, for him, is a

strong indication that the demand for whale meat is clearly declining and that in the not too distant future, the pilot whale hunt will end.

Time will tell.

(With Hans Peter Roth)

*Name changed

Part II: From the Faroese perspective — the pilot whale hunt

Part III: Faroe Islands: Foreign activists provoke patriotic reaction