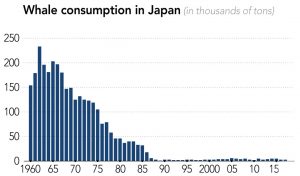

Tradition and culture don’t have much appeal to the younger Japanese generations anymore. The demand for whale meat continues to drop. Image: Sasha Abdolmajid

What are the implications for Japan leaving the International Whaling Commission this summer? Is this devastating news for the whales or a reason for hope?

When the Japanese government confirmed its withdrawal from the International Whaling Commission (IWC) on December 26, 2018, the whale protection community reacted with shock. Japan’s announcement that it would resume commercial hunting in July 2019, left conservationists in fear that the number of hunted whales would rise dramatically and that other nations might follow Japan’s example.

What prompted Japan to leave the International Whaling Commission now and what implications could this have for the whales?

Japan and the IWC

Japan joined the IWC, an international body that had been formed in the late 1940’s to regulate whale hunting, in 1951 as a member. After the IWC-whaling ban in 1982, Japan kept on hunting whales under the pretext of “research”, utilizing a loophole in the IWC regulations. More than 17,000 large cetaceans have been killed by the Japanese whaling fleet since its inception in 1987, mostly in Antarctic waters, which are actually a whale protection zone.

While international criticism for the “scientific whaling” policy kept increasing, Japan extended its influence by successfully “buying” and introducing new IWC members. In return for voting in favor of Japan’s policy, these mostly small nations received “development aids” from the Japanese government. This allowed the country to undermine the moratorium on whaling and to gradually allow commercial whaling again.

The last attempt by the Japanese delegation came on Sept. 18, 2018, at the 67th Conference of Parties to the IWC in Florianopolis, Brazil. It was a controversial initiative entitled, “A way forward”, and it was clearly rejected by 41 to 27 votes. But the rejection was no surprise for the Japanese government. It gave Japan reason enough to leave the IWC, without “losing face” while arguing that the purpose of a whaling commission was to regulate, but not to ban whaling.

An adult and sub-adult Minke whale are dragged aboard the Nisshin Maru, a Japanese whaling vessel that is the world’s only factory whaling ship. The wound that is visible on the calf’s side was reportedly caused by an explosive-packed harpoon. Image: Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

Good for the whales, good for the economy?

Japan also announced that it will end its so-called “scientific whaling” program in Antarctic waters. In the 2017/2018 season alone, this scientific hunt led to the deaths of 333 minke whales killed in the Southern Ocean. Amongst these were 122 pregnant females. By abandoning this hunt, hundreds of large cetaceans’ lives in the Southern Ocean will be spared year after year.

Along with this good news for the whales in the Antarctic, Japan’s struggling economy will also receive a relief. Research whaling expeditions were both costly and highly subsidized with tax money (approx. 30 Million dollars annually). With a further need to replace the aging whaling fleet with newer, more modern ships, Japan was looking at having to come up with several hundred million dollars. These extra expenses can now be saved, along with the financial need for development aid to certain small IWC member nations, likely to be cut.

In terms of international relationships, criticism of Japan’s vote-buying within the IWC, should disappear. Quarrels with Australia and New Zealand over whaling in their backyards or in international marine protected areas, should cease. Humiliating incidents that occurred like via the internationally televised series Whale Wars or when the International Court of Justice ruled that Japan should cancel all existing scientific whaling permits in the Southern Ocean, should also end.

Why did they not stop in 2014?

Japan complied with the ruling of the International Court for one season, then resumed whaling again in the Antarctic in 2016. They could have ceased whaling in 2014 but chose not to. In East Asia, emphasis is placed upon “not looking humiliated”. Japan’s resumption of the Antarctic whaling expeditions in 2016 was a clear statement that it would not bow to international pressure, but rather make its own, sovereign decisions.

There was also the “Whale Wars” with Sea Shepherd, an international environmental organization, which followed the Japanese fleet with its’ own ships, resulting, at times, in violent incidents. Japan would not cave in to a group they declared, “eco-terrorists”.

Are the whales in the North Pacific at more risk?

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

Japan has announced that the resumption of commercial whaling will take place within the Exclusive Economic Zone up to 200 nautical miles offshore. The zone, which is basically reserved exclusively for Japanese commercial activities, is a rather significant area in size, which leaves environmental organizations fearing that whales in the North Pacific are at risk. In comparison to the entire Northern Pacific region however, the marine area of the Japanese Exclusive Zone is not overly large.

Japanese whalers are already commercially hunting cetaceans in this area, they just haven’t called it commercial whaling. Rather, it is referred to as “small-type coastal whaling”.

What lies between the past and the future of whaling in Japanese waters remains to be seen, as the demand for whale meat within Japan is sluggish and continues to dwindle. The Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan’s major newspapers, writes, “companies in the fisheries industry are unenthusiastic about the prospects given international criticism and tepid consumer interest”.

Fisheries Agency statistics state there are around 3,000 tons of frozen whale meat currently stored in Japan, roughly the same as the country’s annual consumption. In 1962 over 230,000 tons of whale meat were consumed, but in recent years, annual consumption has ranged between 3,000 tons and 5,000 tons – 1.5 to 2 percent of what it used to be.

Room for hope

While it is much more convenient to hunt whales within domestic waters – without international quarrels, or the expense of expeditions in rough, cold waters 10,000 miles away, Japan will now be whaling in its own backyard. Perhaps the real economics of demand and supply will at last come into play, rather than subsidized pride in response to outside pressure.

While older Japanese generations may still bear some nostalgia for whale meat, the general consensus is that demand is slowly dying out with younger Japanese generations, who simply don’t care for it. With so little demand, it is entirely feasible to suggest that whaling in Japan might actually die down in the not too distant future, without Japan having to lose face to the outside world.

(With Hans Peter Roth)

1 Comment

Leave our fish alone