Tragically, concepts like the Chinese sparrow-kill from 1958 are still widely applied even nowadays. Please read the following story and find out at the end, what this has to do with dolphins and whales.

China’s Worst Self-Inflicted Environmental Disaster: The Campaign to Wipe Out the Common Sparrow

By George Dvorsky

B ack in the 1950s, China was going through its Great Leap Forward, an effort to transform China from a largely agrarian nation to a thriving industrial Marxist powerhouse. These sweeping (and often brutal) reforms, touched virtually every facet of Chinese life — and as one particular episode in China’s history points out, the animal kingdom was also far from immune. In 1958, China ordered the extermination of several pests, including sparrows — an ill-fated campaign that eventually led to catastrophe.

The Four Pests campaign

Chinese leader Mao Zedong initiated the Four Pests campaign after reaching the conclusion that several blights needed to be exterminated — namely mosquitoes, flies, rats, and sparrows. While many people nowadays would regard tampering with the ecosystem in such a radical way as a shockingly irresponsible idea, this was a classic case of something appearing like a good idea at the time.

According to environmental activist Dai Qing, “Mao knew nothing about animals. He didn’t want to discuss his plan or listen to experts. He just decided that the ‘four pests’ should be killed.”

Moreover, the idea fit in quite well with Mao’s hard-line totalitarian Communist ideology. Marx himself was far from an environmentalist, proclaiming that nature should be fully exploited by humans for production purposes (a legacy which may explain China’s poor environmental track record to this very day).

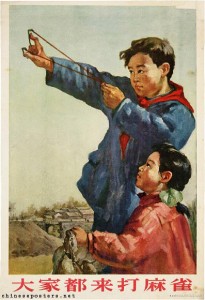

The Great Sparrow Campaign also known as the Kill a Sparrow Campaign was one of the first actions taken in the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962.

Now, while the Chinese citizens were called upon to wage war against all four of these pests, the government was particularly annoyed by the sparrow, or more specifically, the Eurasian Tree Sparrow. The Chinese were having a rough go of it as it was, adapting to collectivization and the re-invention of farming, so they felt particularly victimized by this bird which had a particular fondness for eating grain seeds.

Chinese scientists had calculated that each sparrow consumed 4.5kg of grain each year — and that for every million sparrows killed, there would be food for 60,000 people. Armed with this information, Mao launched the Great Sparrow Campaign to address the problem.

“Total war”

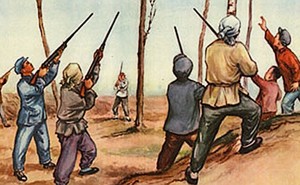

To accomplish this task, Chinese citizens were mobilized in massive numbers to eradicate the birds by forcing them to fly until they fell from exhaustion. The Chinese people took to the streets clanging their pots and pans or beating drums to terrorize the birds and prevent them from landing. Nests were torn down, eggs were broken, chicks killed, and sparrows shot down from the sky. Experts estimate that hundreds of millions of sparrows were killed as part of the campaign.

As a result of these efforts, the sparrow became nearly extinct in China.

And that’s when the problems started.

Famine

By April of 1960, it started to become painfully obvious to the Chinese leaders that the sparrows, in addition to eating grains, ate insects. Lots of insects.

And without the sparrows to curb the insect population, the crops were getting decimated in a way far worse than if birds had been allowed to hang around. Consequently, agricultural yields that year were disastrously low. Rice production in particular was hit the hardest. On the advice of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mao declared full-stop to the Great Sparrow Campaign, replacing the birds with bed bugs on the Four Pests naughty list.

But the damage was done — and the situation got progressively worse. Locust populations swarmed the countryside with no sparrows in sight. Things got so bad that the Chinese government started importing sparrows from the Soviet Union. The overflow of insects, plus the added effects of widespread deforestation and misuse of poisons and pesticides, were a significant contributor to the Great Chinese Famine (1958-1961) in which an estimated 30 million people died of starvation.

The episode serves as a stark lesson for what can happen when sweeping changes are made to an ecosystem. Yet, in a startlingly similar campaign initiated back in 2004, China culled 10,000 civet cats in an effort to eradicate SARS. And according to Tim Luard of the BBC, they have also launched a “patriotic extermination campaign” that targets badgers, raccoon dogs, rats, and cockroaches. The over-arching lesson, it would seem, may not have be learned.

Source: io9.gizmodo.com

What this has to do with dolphins and whales:

Chinas’ 1958 extermination attempts against sparrows show what a devastating impact totalitarian regimes and programs can have – and not only in the short term. Communist and other totalitarian ideologies have left people uprooted; culturally, spiritually and also environmentally. This disconnection from nature, from understanding ecological cycles and the devastating effect of blindly intervening in the environment, especially on a huge level comparable to the Chinese sparrow extermination programme, has led to environmental and human tragedies of almost unimaginable magnitude.

Yet tragically, such disconnected black and white concepts are still widely propagated and applied nowadays. For example, the Japanese fisheries ministry views whales as the ‘cockroaches of the sea’ and wants them, and also coastal dolphins, to be hunted down for ‘pest control’.

In governmental propaganda logics, this means that cetaceans eat too many fish that are meant for human consumption. This ignorant concept does not acknowledge that the real problem is overfishing. In fact, cetaceans are being blamed for a human caused problem: lack of fish as a result of human industrial overfishing.

This black and white governmental propaganda logic is completely against anything that makes sense, also scientifically. It is acknowledged – obviously also by Japanese fisheries propagandists – that fish stocks have collapsed and continue to decline.

There is also little debate about the fact that the big baleen whales – the whodunits according to pro whaling propagandists – have been decimated to about 10 percent of their original populations over the past 150 years, as a result of industrial whaling. So if the whales were the cause by eating too many fish, fish stocks should have increased tremendously by now, with most of the large whales gone today… Right?

Another example that nature is not as simple as the propaganda logic suggests, is the paradox that the near-eradication of the blue whale in the waters of the Antarctic during the 20th century led to a paradoxical fall-off in krill, the small shrimp-like creatures on which they feed.

The ‘Antarctic Paradox‘ results from a biological cycle in which the whales play a key role in providing iron to the surface waters needed by the algae on which the krill feed. The whales release the iron in their excrement, restarting the cycle from algae to krill to whale. When numerous, whales maintained a very productive ecosystem as environmental gardeners. It collapsed with their decimation.

By Hans Peter Roth & Sasha Abdolmajid